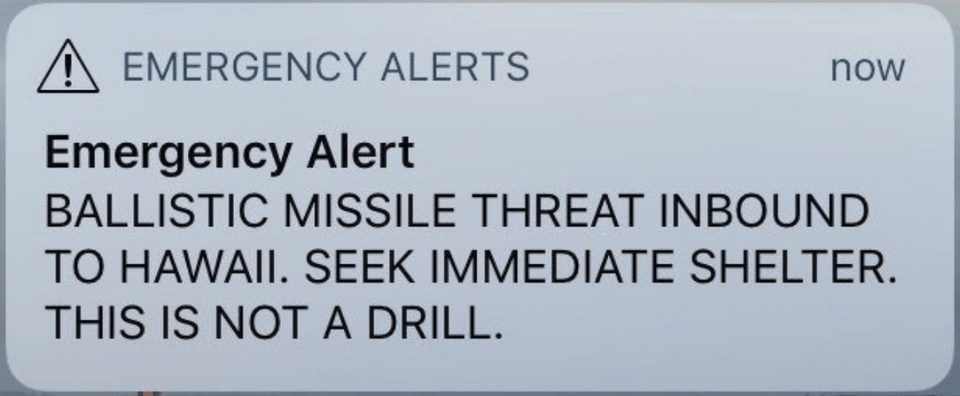

You may remember this alert from 2018, when a ballistic missile warning went out to the people of Hawaii. If you don’t remember it, that’s OK—it turned out to be a false alarm. Although the full cause was never made public, there was widespread speculation that it stemmed from a poorly designed UI—the user interface for the alert system—which made it dangerously easy to click the wrong option and send a real alert instead of running a test.

The design of our tools can make the difference between something valuable, useless, or even dangerous. We see this in medicine all the time, with examples ranging from similar-looking medication vials, to alarms that go off so frequently they’re ignored, to non-ergonomic devices that lead to overuse injuries.

The current mantra about AI in healthcare is that people will work with AI rather than be replaced by it. So the very next question is: how will we work with it? Like any tool, we have to design the human interaction intentionally. And since this wave of AI is focused on helping us think, we need to understand how people think and the shortcuts we tend to take.

Here are three important biases to keep in mind:

In an episode of the US version of The Office, Michael Scott drives into a lake because the GPS tells him to—even though he can see the lake. That’s an exaggerated version, but the real-world equivalent is everywhere: GPS routes we follow without question, product recommendations we take without looking further, or calculator results we believe even when they contradict our own math.

Automation bias is our tendency to trust computers more than ourselves.

The challenge is designing an interface that lets people override automation when appropriate and knowing when it’s appropriate. People are already using design elements to prevent this: having AI algorithms show uncertainty levels, illustrating the “reasoning’ behind automated opinions, or having the user make their own decision before revealing the AI’s recommendation.

The second bias I want to discuss comes from the fact that attention is a limited resource—even for the most diligent among us.

You’ve probably seen videos of people asleep at the wheel of their Tesla in autopilot mode. A disclaimer might say “the driver is still responsible,” but while that might shift legal responsibility, it doesn’t help someone stay focused when the car appears to be handling everything fine—for now.

This is called inattention bias, and it happens when people are lulled into inattention by repetitive tasks.

We see this in bias in radiology with speech-recognition dictation software. Report templates often come with “default normals” or pre-filled findings that assume everything is normal unless edited. Since most exams are normal, this saves time. But after reading dozens of reports, it is easy to miss something and accidentally leave in an incorrect “normal” statement.

When we built our own in-house dictation system, we required radiologists to take a small action—click a button or speak a command—to insert normal phrases. It created a tiny speed bump that we hoped would disrupt inattention bias. We didn’t collect data on whether it worked at scale, but it was a deliberate design choice.

The third bias is one that should feel familiar to all of us. I call it laziness bias, and it’s our tendency to take the easy path, even when it’s not ideal.

Amazon loves this bias. You could go to the manufacturer’s website for a better price—but it’s so easy to add the item to your Amazon cart and check out with one click, you just do that instead. Less friction=more sales.

Laziness bias shows up in healthcare too. With so many clicks, forms, and documentation requirements, people naturally look for the most efficient route forward.

For example, I’ve seen doctors order a CT scan with the reason listed as “follow-up of pulmonary nodule”—even though the patient had no such history. Why? Because selecting that option triggered the exact test they wanted. They didn’t realize that the radiologist might include that incorrect history in the report, leading to a false record of a nonexistent nodule.

I strongly believe AI can supercharge healthcare—boosting both efficiency and quality. But only if it’s designed thoughtfully. Creating good tools means understanding our human tendencies and designing with them in mind.

So the next time you hear about an AI system that helps doctors answer messages, write notes, or summarize conversations, ask yourself:

- Will humans actually check the results?

- How will the system keep people engaged and avoid inattention bias?

- Will it make errors easy to fix, avoiding laziness bias?

- Will people have enough knowledge and freedom to override the system, avoiding harmful automation bias?

But beyond simply avoiding these biases, we can also leverage them:

- How can we use laziness bias to make the right path the easy one?

- Can AI recommendations become so reliable that inattention bias is earned?

- Can we build systems so trustworthy that automation bias leads us away from flawed human instincts—and toward better outcomes?

Keep an eye out for the best AI tools, the ones that think with us—not instead of us.